Summary:

- Cosmology and Human Role: Cosmology has two meanings: scientific investigation of the origin and development of the universe, and a broader view that includes the human role in the universe. Scientists focus on physical origins, while philosophers and writers explore the human connection to the cosmos.

- The Mystery of Laws: Despite scientific progress, fundamental questions remain. For example, why do the laws of nature exist? Newton’s law of gravitation predicts but doesn’t explain gravity’s origin. Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc², is another example of a profound mystery.

- Mathematics and Experience: Mathematical equations not only predict physical phenomena but also offer a unique experience. Scientists immersed in mathematical worlds often encounter a higher state of consciousness. The equations themselves deepen the mystery rather than explaining it away.

- Emerging Wisdom: The interplay between science and spirituality can lead to a wisdom tradition. As scientific understanding matures, it may converge with spiritual insights, creating a richer understanding of reality.

This interview highlights the ongoing exploration of our place in the cosmos and the profound mysteries that science and spirituality both seek to unravel.

Full transcript:

Rick Archer: Welcome to “Buddha at the Gas Pump.” My name is Rick Archer. “Buddha at the Gas Pump” is an ongoing series of conversations with spiritually awakening people. We’ve done over 660 of them now. If this is new to you, and you’d like to check out previous ones or other ones, go to batgap.com, BatGap, and look under the “Past Interviews” menu. I also encourage you to subscribe to the YouTube channel. I’m hoping we’ll hit 100,000 subscribers this year, not that it makes a huge difference or anything, but we’re close, and it would be fun just to hit that mark. This program is made possible through the support of appreciative listeners and viewers. So if you appreciate it and would like to help support it, there’s a PayPal button on every page of the website, batgap.com, and there is also a page explaining some alternatives to PayPal.

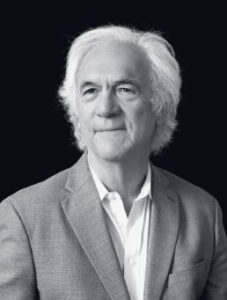

My guest today is Brian Thomas Swimme. Brian did his doctoral work in Gravitational Dynamics in the Department of Mathematics at the University of Oregon. From the publication of The Universe is a Green Dragon, which is his first book, to the Emmy-award winning PBS documentary, “The Journey of the Universe,” Brian has articulated the cosmology of a creative universe, one in which human intelligence plays an essential role. For three decades as a professor in the Philosophy, Cosmology. and Consciousness Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco, he taught Evolutionary Cosmology to graduate students in the humanities. Currently, he is the Director of the “Third Story of the Universe” at the Human Energy Project, a nonprofit, public-benefit organization. And I must say that, ever since I first heard about Brian some years ago, I was really excited to have him on BatGap, and I’m really happy that we are finally doing it. And I just spent the last week — I don’t know, 16,18, 20 hours — binging on everything I could get my hands on that Brian has done: his new book, Cosmogenesis; a lot of great little videos on the Human Energy Project YouTube channel, which I’ll provide a link to on his BatGap page; and there are also a lot of talks that he has given which you can find on YouTube if you just search for his name. Anyway, thanks, Brian. It’s marvelous to finally connect with you.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Great to be here, Rick.

Rick Archer: Tell us what a cosmologist is.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. It’s a word that has two separate meanings, really. In science, it’s the investigation of the origin and development of the universe. And the great excitement of the 21st century is to have the confidence to say something about the birth of the universe from a physical standpoint. So that’s what a cosmologist is in the world of science. But in the humanities, it has a different meaning: a cosmologist is someone who may speak of the birth and the development of the universe but includes another really important part, the human role in the universe. So this is something that scientists don’t pursue, but philosophers and writers do. So I love the word. So it works both with science and humanities. However, what I’ve discovered over the years is that neither of those meanings is the dominant meaning in the contemporary mindset. When I’m talking to people just casually, and I say I’m a cosmologist, they will more often than not assume that I work with hairdos and mascara. Yes, I’m serious — all the time. Yes, it’s happened for years and years.

Rick Archer: Yes, well, you’re a very unlikely cosmetologist. In the humanities area, those who call themselves cosmologists, are they just really metaphysicians who are just coming up with intuitive feelings? Like, for instance, I am not a scientist. I don’t have mathematical training; I couldn’t pass high school algebra. Well, maybe I could if I took the courses again. But I’m probably a cosmologist in terms of your second definition, which is that I’m always speculating about this stuff and thinking about it, and so on.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, I would say that in the realm of science, for the most part, the vast majority of scientists would insist that there’s one methodology for arriving at knowledge, but I think that’s far too strict. There are multiple ways of arriving at understanding and real knowledge, and one of the most powerful is intuition, and certainly I would consider you a cosmologist with that meaning. There are many people in the humanities who will begin with an understanding that comes from the sciences in terms of the evolution of the universe and then will expand upon that. I think it’s a great service that that these writers and thinkers provide, because as scientists, we’re not trained to think that way. And actually, usually, when we do, it doesn’t come off well because it sounds like sophomores in high school arguing about things. So we really need each other. I mean, the sciences and the humanities really do need each other.

Rick Archer: For a couple of years, I’ve had a little chat group going with a dozen friends, half of whom, I would say, have a materialist perspective; they think that consciousness is produced by the brain. And even though this half has been meditating a long time and doing spiritual practices, they don’t attribute any cosmic significance to their experiences. For instance, they’ll say something like, well, you can experience vastness, or you can experience the sense that you are one with the universe, or that you look at a tree, and you see yourself in it, or any of these kinds of experiences, but you’re just reading those interpretations into it. It doesn’t mean that you’re really one with the universe, or that your consciousness is really unbounded; you’re just having that flavor of experience. You could have it with psychedelics or anything else. The other half of the people in this group, say, no, actually, the human being is so wired that they can — you used the word “intuitive” — that they can intuitively or even directly, experientially cognize the deeper realities of the universe, and, and if consciousness is fundamental, and if it is a vast field, an unbounded field, then the brain is more like a transmitter- receiver than a producer of it, then they can actually know that with confidence, with certainty, with authority. But it’s very, very difficult to convey to another person, particularly since even other people who actually have an experience along those lines might give a completely different interpretation to it. So I don’t know; what’s your reaction to all that?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Well, there are all kinds of deep things happening there, and I don’t pretend to be able to unravel them. But I am really intrigued by that ongoing conversation that you’re having with your friends, that I think we as contemporary humans are having; it is this relationship between the human mind and the universe. I mean, it’s just, like, wow! Kind of the default position that really dominates, I would say, in the universities today, is that we are ontologically separate from the universe. And it’s not, I mean —

Rick Archer: Explain what “ontologically separate” means for the audience.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, I mean, it’s that when I say “in the default position,” it’s not as if people, for the most part, the general population reflects on this. I think what I’m talking about is the basic assumptions that are given to us by our parents, by our schools, by our religions: the basic assumption is the human mind has the power to understand the universe out there, and the universe out there is conceived to be something that is somewhat mechanical. And people use the phrase “inert matter” or “lifeless matter” or “dead matter.” So that we modern Americans, modern Europeans, we just wake up in a world that takes for granted that we are here inside of our heads, and we’re looking at a universe “out there” that is beneath us, meaning it’s less complex, less intelligent. It’s more dead-like. But if that’s the unconscious beginning point in a conversation, the tension can’t be resolved, I believe.

Rick Archer: So far it hasn’t been.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, it goes on and on, but here’s my basic take, how I would enter in. I think that the discoveries of scientific cosmology in the 20th and 21st centuries really do allow a different starting point. So here’s my little way of summarizing everything I think about these weighty questions. I have this image of a scientist who is in the laboratory, and he’s investigating the structure of brains, and the specimen he is focused on is that of a fish. So he’s checking out the structure and the dynamism of the brain, and this moment comes when he realizes, just like, wow, it’s so complex; it’s amazing! Now he’s talking about a fish brain, and he’s overwhelmed with a sense of just happiness, that he has lived this life that enables him to have this deep understanding. And then he thinks about all that was required, as he thinks of his professors and the years of training that it took. And then he thinks of his parents, and they helped him go through college, and then his grandparents. And then he goes back further, and he starts to express gratitude for himself for his own brain. Like, wow, how wonderful to have this kind of brain! And then he takes the next step, and he realizes that the fish he’s studying was the ancestor that gave birth to his brain. So all of the mammalian brains really come out of the creativity of fish brains; fish brains are far more diverse than mammalian brains. So there’s this moment when he realizes he is examining one of his own ancestors that enabled him to have this power. So you see, that is a different kind of scientific knowledge. That is, in a real sense, that’s knowledge of oneself. You know, they have a phrase for each of us. Each of us is a cosmological construction that took 14 billion years. So with that starting point, you see, we realize that when we are speculating — I’m going back to your point — like, when you and your friends and anyone is speculating on the nature of the universe, that is, in a very literal sense, the universe reflecting upon itself. And so, that to me is the excitement, is that we are waking up to the fact that our knowledge is self-knowledge. It’s the knowledge of a cosmological being, which is who we are. So I guess when you asked me the question, what about the ontological difference between ourselves and the universe is that there is none, not really. We are a further development of the universe. So I get kind of carried away, Rick, but I mean, that is my orientation.

Rick Archer: So do I. Yeah, that’s great. Probably a dozen times over the years in various interviews, I’ve quoted that quote of yours, where you say, leave hydrogen alone for 13.7 billion years, and you end up with rose bushes, giraffes, and humans.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes.

Rick Archer: And there’s a lot in that quote, actually, because if the universe is some kind of random accident or totally mechanistic or anything, why should we end up with rose bushes, giraffes and humans? I mean, why should there be this tendency to our greater complexification of forms and species over the billions of years? Why shouldn’t it have just ended up being rocks or nothing at all? And you could actually perhaps throw in here the thing about Stephen Hawking’s discovery that if the universe were expanding faster or slower by a factor of what was it, ten times — you tell me the statistic — there wouldn’t have been a universe? I mean, to me, this speaks of the existence of some kind of intelligence, which we can explore further in our conversation, which has given rise to and orchestrated this whole thing.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, that’s how I think of it as well. Exactly. It’s a form of intelligence that we’re only just beginning to explore, really. So it’s not like a big human; the universe isn’t a big human, but it’s — wow, it’s amazing.

Rick Archer: It’s a green dragon, right?

Brian Thomas Swimme: You know, for a while — it was about 20 hours — there was an announcement made by astronomers that they had averaged out all the light in the in the universe, and they said the basic color was green —

Rick Archer: Oh, cool!

Brian Thomas Swimme: — and so, I thought, for like, 20 hours, I thought, oh, my God, it is a green dragon! Yes, but then they corrected it. It doesn’t (overlapping).

Rick Archer: Well, this thing about intelligence, for instance, I’ll read you a quote from this guy, one of the guys who are in that chat group. His name is Jason, and he said, simple laws of physics and chemistry are sufficient without the need to invoke this field of all-pervading intelligence. I said, maybe, but maybe we have to invoke this field of all-pervading intelligence in order to account for these simple laws and their continued functioning. Another guy said to me — it might have been Jason — he said, well, yes, just look at the periodic table of elements; it’s fantastic, and from there, we can build the whole thing. And I said, yes, but that’s way too emergent. I mean, how the heck did that come to be? So people have this tendency to not take it down to basics enough. Another guy said to me, you know, grant us one miracle, that the laws of nature exist, and we can explain the whole rest of it. And I said, no, can’t grant you that miracle; why do those laws of nature exist?

Brian Thomas Swimme: I like that: grant us one miracle. Yes.

Rick Archer: So, anyway, what do you think? I can keep probing you with more things, but I want you to do most of the talking.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Well, no, I mean, I guess I would say this: Wittgenstein is a pretty smart guy, and he said — I can’t quote him exactly, but he basically said something like, one of the greatest stupidities of the modern world is to think that the laws of the universe have been explained. Okay, so what is he getting that? Why would somebody with Wittgenstein’s intelligence, how would he arrive at such a statement? I mean, it’s almost universal that we contemporary humans think we’ve explained the laws of the universe. What’s he getting at? Do you see what I mean? It’s a startling statement, but then I’m going to add one more to it with someone who’s alive, Noam Chomsky You know, he made this amazing statement, and it was at a conference down in San Diego. He was quoting from Isaac Newton, and he said, if anybody thinks that my universal law of gravitation explains gravity, they are an idiot. No, so in other words, they’re saying the same thing, in a way. They’re saying something very, very similar.

Rick Archer: So was Newton saying there that his law perhaps explains how gravity behaves, but it doesn’t explain why there is gravity? Was that what he was saying?

Brian Thomas Swimme: That, definitely. That’s the huge point is that why is there gravity? That’s not explained in the least bit, but even more, in the sense that Newton doesn’t explain how it operates. See, that’s what I ended up studying in grad school is gravity, and the stunning thing about Newton’s equations — and then following him, Einstein; they’re both similar in that they articulated equations that enabled us to make astounding predictions — but to be able to predict the numbers that will show up in a future experiment is different than explaining the nature of the laws themselves. So I guess I would want to just lift that up.

And then a third mind that I’d want to bring into the discussion is Alfred North Whitehead. He regarded the laws themselves as fundamentally different from the mathematical formulations of the laws. So you have that distinction right away, and just sort of bear that in mind. And that the mathematics — I’ve been repeating myself here — does not explain how the laws themselves function. And Newton was asked this question directly about, well, how does that work; how does it happen? And he said, I don’t make hypotheses, so he backed away from that. He just published the mathematical equations. He showed the way in which they make predictions. So, and I can’t now tell you what they mean, right? I’m not now saying I know. I’m saying that there’s a fundamental mystery to the very fact that the universe is orderly that is appreciated by these deep thinkers. And I think the modern mind becomes lazy when it thinks that these things have been explained entirely, and I’m not talking about, like, the general populace; I’m talking about the some of the finest scientists. Steven Weinberg believed that we could explain everything — one of your interlocutors said this — we can explain everything just knowing what took place in the first several minutes of the universe. But that’s not true. I mean, and I know you know, this, but just to give you a sense of where I’m at, the complexities that emerged out of the universe are not present in the equations of gravity or the Strong nuclear interaction. Those complexities are an emergent quality of the universe. So my basic stance, for better or for worse, is that we are inside of an amazing mystery that enables us to apprehend certain qualities such as order, but a universe that is constantly transcending itself in terms of what it’s bringing forth. That’s just how I go about my day thinking.

Rick Archer: Yes. Well, what you just said actually segues into something that I’ve been discussing with our mutual friend, Tim Freke. Tim seems to have this philosophy — Tim, for decades, wrote books about and kind of jibed with the classical understanding of the Vedanta philosophy and others, that there is a fundamental field of consciousness, and that the universe somehow manifests from that and then becomes more and more complex, and so on. And that’s basically what I still ascribe to. But his idea is that, no, there is no — in fact, I can quote from him here. He refers to an ocean of intelligence or consciousness as mythological and says that if you need intelligence first, before you can get intelligence in the universe, that is just infinitely regressive, and gets you nowhere, because you need intelligence to get that intelligence and back forever. You just make the big God claim. The intelligence is just there, no reasoning, just a bold insertion of belief. That’s what makes this idea so much weaker than the modern ideas from science. And I would say, why not the big God claim? Why not a field of intelligence, which periodically rises up in manifestation, and then eventually collapses back into pralaya, as they call it in Sanskrit — this sort of cosmic rest period — and then rises up again, and perhaps is doing so simultaneously in multiple universes? And Tim’s idea is that somehow the universe pulls itself up by its own bootstraps and just becomes increasingly conscious as it evolves. And I counter, well, how could it do that? There must be laws of nature, or like you were just saying with Weinberg, who said you can explain everything from the first what, a few seconds or something, there must be inherent, even before there’s any big bang, there must be inherent in that from which the Big Bang sprang all the potentialities that we eventually see expressed in the manifest universe, and they just become more and more expressed, more and more manifest as time goes on, but you don’t get something from nothing. Anyway, I think I’ve stated it; I don’t want to carry on too long. But that’s how he and I kind of go back and forth on this, and where would you fit in?

Brian Thomas Swimme: But how would you characterize — so you talk about a field of intelligence, and how would Tim — he would object to that, but how would he want to phrase it?

Rick Archer: I’m not sure. He thinks that intelligence — or God, even, if we want to use the word God — doesn’t exist in some primordial sense, and it’s actually coming into being anew along with the manifestation of the universe. And I say to that, fine if we’re talking about the manifest aspect of God, or intelligence, but there’s also the unmanifest, and the manifest arises from the unmanifest, like waves arise from the ocean.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. I know in a certain sense, my response will be a disappointment, but —

Rick Archer: No, I don’t care. That’s all right.

Brian Thomas Swimme: — oh, good. Good.

Rick Archer: You can disagree with me. And maybe you can dissuade me from looking at it that way. It’s just so far, I haven’t gotten what he’s saying.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, and I don’t claim to know. And this, now we get kind of personal. I’m not impressed with my own orientation or anything, but I just want to just explore it with you a little bit. And that is, when I was when I was in my 20s, I did nothing but mathematics. I just lived in that realm, and I loved it, and I still love it. But I made a move in terms of consciousness that Alfred North Whitehead, to bring him up again, said was one of the fundamental mistakes of modern cosmology, and that is, he calls it “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” And it’s a long, fancy phrase, but what it means is simply that we humans — and he meant not just Europeans, not just Americans, but really, the human condition — makes us vulnerable to this fallacy, and the mistake is to identify reality with what is essentially an abstraction. And so in my case, it was the equations of mathematical physics. I didn’t actually say this out loud; I didn’t know enough philosophy to be able to say it out loud. But, later, looking back on it, I realized that, but I was working with the equations. And I think this is true of most mathematical scientists: the equations themselves became reality. They really did, or if you like, they became the secret code of the universe, that this was the order of the universe. And what I came to understand is something different. And this is where — I’m getting now to my response to your question — that science has enabled amazing things, especially when we think about technology. I mean, it’s just, it really is incredible, the power of science. But there’s another power that it provides that I don’t think has been sufficiently explored, and it’s what I’m exploring now, and it’s easy to state. It’s that, at its best, the mathematical equations enable us to participate in the universe in ways that can become beneficial for us in actually changing things in a way that helps humans and other forms of life. And in addition to all of that, which I affirm, the scientific understanding, the mathematical equations, enable a new experience of reality, and it’s that new experience of reality that has become my main focus, my main interest. Just think of all the different ways we have to experience reality. I’m just suggesting that the equations themselves enable an experience that hasn’t been appreciated, or even it happened in the history of humanity. So as I’m making this gigantic claim — and I don’t want to pretend like I have control over all of the meaning that I’m touching on; I don’t — I feel like we’re just beginning to step into this. And I gave the example of the ichthyologist working on a fish brain, and that would be an example of what I mean. I mean that that scientific understanding that comes from our discovery of evolution, that scientific understanding enables a relationship, an experience that is unlike previous experiences of the depths of things. I’m not saying it’s better. I’m going to be really clear: I’m not saying it’s better than the various cultural means of deep experience that have been discovered and cultivated for millennia. I’m simply saying it’s a new one; that’s all I mean. It’s a new experience of what I would call, in traditional language, the sacred; it’s a new touch into the sacred. So that’s how I’d respond to your question.

Rick Archer: We were talking earlier about the possible ontological connection between the individual and the universe, and I guess, in my simple terminology, I would describe that as being — that whatever our essential nature is must also be the essential nature of the universe because we’re part of the universe. And in spiritual circles, people say, okay, well that essential nature is — they sometimes call it “the self” or “pure consciousness” or “Brahman.” There’s this sort of underlying foundation. That’s redundant, but there’s a foundation which is pure consciousness, which is being, which has qualities such as intelligence and bliss and things like that. So there’s that. And if that’s the case, then it ties right in with this whole idea of, could the universe have come out of consciousness or some field of intelligence, and so on? And could its purpose in coming out have been to eventually give rise to beings such as ourselves and perhaps much more highly evolved beings who could have these kinds of conversations and cognitions about what reality is? In other words, for the reality of being to become a living reality — a living, breathing, acting, loving reality rather than just an abstract one, which kind of fits in with the Sanskrit idea of leela or play. It’s, like, more fun for God to be doing all this than to just lie there in its cosmic ocean and do nothing. I’ll let you bounce that back before I have you express another thought.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Well, I guess as you’re talking, I just feel these qualities wanting to come forth. You know, it’s a lovely feeling. And then, the other thought, as you were talking, I thought, I wonder, I mean, when we first emerged, we, sapiens, maybe 200,000 years ago, maybe 300,000 years ago — it’s impossible to put a start, because it’s a continuous evolutionary process — but I just try to imagine myself back there, living in a group of, say, 20 individuals, and trying to find our way forward and succeeding; we’re descendants from the ones who succeeded. And the sorts of things that they would know, they learned some amazing things, for sure, about the universe and then other things that were not so helpful or dropped off. But then there are these moments when the human populations would move into experiences that we’re new, so it’s easy for me to imagine, and, in other words, it seems commonplace to think that there they are in Africa, and none of them are having experiences of a field of intelligence filling the whole universe — and then they were. In other words, there was a discovery made, and then it’s all written down and celebrated in the Axial Age. So now, we developed ways of bringing forth these amazing qualities that we now call divine, right? Like you say, love and compassion, and so forth. So I tend to think that those are great discoveries. And I wonder, I mean, I know that I would be really happy myself in one of these metaphysical formulations. Because right away, as you started talking, I just feel my spirit lift and become lighter. But I’m also thinking, possibly, that this new breakthrough that we call the evolutionary cosmology, I think it is going to develop its own processes for evoking experiences that may be very similar to what’s in Vedanta and other systems, maybe even identical; I don’t know. But as much as possible, I try to stay with and deepen my own experiences in this just to see if something beneficial might arise, and it takes all my time. What I would love is, and I think in the future, there will be a profound engagement between these various spiritual traditions, but the scientific will have blossomed into a wisdom tradition. It’s not there yet, but that’s kind of the crazy intuition I have, and I’m just trying to be part of the maturation of the scientific venture.

Rick Archer: Oh, me, too, and that excites me a lot. I don’t have the scientific chops that you have, obviously, but I’ve been doing the spiritual thing for 54 years or so in this lifetime.

Brian Thomas Swimme: You’re 54?

Rick Archer: No, no, I’m 73 —

Brian Thomas Swimme: Oh, good.

Rick Archer: — but I’ve been meditating for 54 years. I’d be a little bit weather-beaten if I were 54. But I’m just saying, I’ve always been as excited as you are by the interplay of science and spirituality —

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, yes.

Rick Archer: — and I think that the two complement each other and can potentially provide what the other lacks.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, yes, exactly. Right. Yes, I agree completely. That’s why it’s so great to be alive now.

Rick Archer: Yes, it’s exciting!

Brian Thomas Swimme: I mean, this is so exciting. And to think that, you know, just even a couple centuries ago, there’s no way you could have this kind of interaction, that we were all split up, you know, on separate continents and so forth.

Rick Archer: Yes, and you’re getting burned at the stake for talking about this stuff.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, just think of it. You know, it’s so easy to be concerned about the way things are going now, but I really do think it’s important for us, those of us who are drawn to it, to celebrate how fantastic it is.

Rick Archer: Yes. Boy, like, bubbling in the back of my mind are about six questions I want to ask you, but I want to tie up some things we’ve already talked about. You were talking about mathematics, and how it somehow evokes a state of consciousness or a way of experiencing, if you can really do the mathematics, that you otherwise wouldn’t have, and I imagine that would be true. I’ve never been able to do it, but I can imagine someone like you, or, you know, some of the greats, like Einstein or Hawking, and so on, just being so deeply into their mathematical world that it’s like a higher state of consciousness.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. Yes.

Rick Archer: And haven’t various people marveled at the fact that mathematics even works? I mean, that it has this correlation with the way the universe works and that we’re actually able to come up with this language which so precisely matches or correlates or predicts what’s happening in the universe?

Brian Thomas Swimme: We have that, and in fact, that would be one of Einstein’s most powerful experiences was just the stunning realization that the universe is comprehensible.

Rick Archer: Yes. I mean, why should E=mc²? How is it we can have this little equation that actually describes the speed of light and its relation to matter, and so on?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Exactly. Exactly. And going back to what I was saying earlier about how the equations don’t really explain the natural processes; they’re movement into an explanation, but not a final explanation. So in a way, I mean, I don’t want to be seen as someone who is throwing out science at all. But what’s amazing is, just like you say, E=mc² — no one knows why that is. Where did it come from? And what does it say? And so I think this is one of the biggest things for me, is that the science doesn’t explain away mystery. If you reflect on it, it deepens the mystery.

Rick Archer: Yes.

Brian Thomas Swimme: It’s just, well, E=equals mc². Seriously? You can think about that for the rest of your life, you know? I mean, that would be an example of the kind of experience that’s possible that’s related to looking at some sacred Sanskrit phrases, or Aramaic, or whatever sacred scripture you look at. The equations are like that.

Rick Archer: Yes. You were also talking about Paul Dirac in one of your videos and how he kept coming up with this “10 to the 40th” and how that seemed to correspond to a whole bunch of different things at different scales, and it’s another one of those jaw-dropping connections.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, he (overlapping). Absolutely, and he just touched upon an order that was expressed mathematically, but then the implications were just stunning. And this research is ongoing, and it’s also contested; there’s nowhere near consensus on this. But nevertheless, Paul Dirac, Nobel Prize in Physics, I mean, he’s a genius, no question about it. And he stumbled on this insight into order via the mathematics and ends up with a view of the universe that celebrates our existence as something that was built into the universe from the very, very beginning. I mean, it just — it changes me spending these years thinking about it. But it’s open-ended; it’s still happening. But I’m glad you picked up on Dirac. I’m so amazed by him.

Rick Archer: And not only our existence. I mean, we might be sea slugs by comparison with some of the beings that may exist in this universe, and we may have a long way to go.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Sea slugs! (Laughter)

Rick Archer: Yes.

Brian Thomas Swimme: I like it! (Laughter)

Rick Archer: But that would sort of lead us into your main work these days, which is the Human Energy Project and the noosphere, and so on. And as I understand it, that all arose from your — I believe you met Teilhard de Chardin, and then you had a close relationship for a long time with Thomas Berry. So talk about those things a little bit. Like, how you have piggybacked on what those gentlemen did and your friendship with Thomas Berry and who he was, because many people won’t have heard of him, and we’ll get into a whole discussion of what the Human Energy Project is doing.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Great. But I need to say I wish I had met Teilhard de Chardin. I have not.

Rick Archer: Okay. I misunderstood. I was hearing some video or something.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. No, wish, I wish.

Rick Archer: Jean Houston did. Do you remember her story?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. I mean, I wish I could tell the story.

Rick Archer: She ran into him in Central Park and knocked him down, actually, when she was 14.

Brian Thomas Swimme: That would have been something. So he is the principal philosopher, theologian, really, but fundamentally, he’s a cosmologist. So for those listening who don’t know him, he was a French paleontologist and a Jesuit priest. My way of talking about him is that he is the first person to get a glimpse into what can be called the sacred dimension of evolutionary time. So evolution was really just discovered, and he was one that took it further, in a spiritual sense. And then Thomas Berry, who died ten years ago, was my teacher for years and years, and just a fabulous guy, a cultural historian. So he spent most of his time working on the spiritual traditions of Asia as well as Europe, and he underwent a profound immersion into the wisdom of Indigenous people. So that was so great to be able to get a feel for the spectrum of the wisdom traditions, yes. And going back to your question about the field of intelligence, and so forth, which could be called God, one time — I would write things and send it to Thomas, and I was reflecting on the nature of God, and he said: Don’t do that. Don’t reflect on the nature of God. I said, why not? People want to know about God, and he said, yes, but you’re not the one to teach them. You haven’t thought about it enough. So I’ve always shied away from making many statements because I’m not a scholar of religion or spirituality.

Rick Archer: No, but the thing is, Brian, you’re a scholar of the universe and the history of the universe and the mechanics of its manifestation, and so on. And I think we can’t really, fully appreciate God unless we understand that. So I think what you have to say, like I said a minute ago, science and spirituality enrich one another. And without science, spirituality has fostered all kinds of wacky ideas, you know?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes.

Rick Archer: And without spirituality, science is rather stale, and you have statements such as from my friend Jason here, which says,” All indications so far is that creation is random and motiveless.” So I really think the two of them need each other to fulfill and further their missions.

Brian Thomas Swimme: I agree completely, yes. And that was also Teilhard’s point of view. Just because we’re talking about him, he offered this, to me, really wonderful insight. He said that people in the modern period tend to think of religion as kind of decaying and having lost its promise. He said, on the contrary, the religions are going to grow ever more pervasive and powerful in the sense of wisdom as they learn to understand themselves inside the evolutionary context. That was his point, is that, certainly Catholicism and Protestantism, they’re locked into a medieval and early modern understanding of things. So, once again, I get all excited thinking about, wow, we don’t even understand. We don’t understand what Buddhism is. We don’t understand what Christianity is. We will only understand it as we see it unfold inside this new era.

Rick Archer: That’s very true. There’s a great quote from Carl Sagan; I was just about to pull it up, but it’ll take too much time. But he says something like, religion should rejoice over the things science is discovering because it’s indicating that God is much grander than they supposed. But unfortunately, they all tend to say, no, no, no, our God is a little God, and we want to keep him that way. But to me, when I use pictures of galaxies, and especially now with the Webb telescope, new pictures from that as my desktop background so I can look at this stuff all day because it gives me a spiritual experience; it evokes awe and reverence.

Brian Thomas Swimme: That’s great.

Rick Archer: Yes. Incidentally, I want to just stick in a nice little comment somebody sent in here, and then we’ll continue with what we were discussing, but this is from Lisa Field in the Virginia mountains. She said: I began seeing “Canticle to the Cosmos” episodes when I was 28 and very much in despair over the timbering, chip mills, songbird species losses, etc. I loved God through nature, so it was a deep grief for me. Thanks to Brian Swimme’s joy-based, powerful teachings, I started two conservation groups and a land trust in Tennessee and Virginia. We saved thousands of forest mountain acres in the Cumberlands and southwest Virginia, et cetera. Thank you. Great Soul.

Brian Thomas Swimme: O-h-h-h.

Rick Archer: How do you like that?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Lisa, Lisa, thank you. Wow.

Rick Archer: Do you know Lisa?

Brian Thomas Swimme: No, but I mean, anybody who could pull that off, and, just — wow.

Rick Archer: Yes, isn’t that — you inspired her to do that.

Brian Thomas Swimme: That’s fantastic.

Rick Archer: Isn’t that cool?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. She’s the great-souled one. Wow. Yes, that’s fantastic. That really cheers me up.

Rick Archer: So mapping the noosphere. Define the “no-oh-sphere”, or “no-ah-sphere”? Am I mispronouncing it?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Well both are — both. I use no-ah-sphere , but both are used, absolutely. The simplest definition is the noosphere is a united humanity. That’d be the simplest way. The next level would be the noosphere is the next stage of Earth’s evolution. So, scientifically, we know the Earth began four-and-a-half billion years ago as molten rock, and then the oceans came forth. And so we can call that the geosphere. And then life emerged in various complex ways and then spread out over the whole planet and then altered the atmosphere, for instance, and we call that the biosphere. And then humanity emerged and coming out of the geosphere, coming out of the biosphere, but with a power that the other living beings did not have. And this new power enabled it to actually spread out over the planet and become as powerful as the geosphere or the biosphere. I mean, in the simplest sense, that humanity now alters the atmosphere each year more than all of life considered together. In other words, we’ve matched the power of the biosphere. But it even goes further, and this is going to be hard to believe, but humanity now moves more of the material of Earth than the winds and the tides and the volcanoes all together. Humanity moves the Earth more.

Rick Archer: Just by digging things up, you mean, and mining, and that kind of stuff?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, exactly — building and transporting goods, you know? I know as I say that, of course, that what comes into our minds is, yes, but look at the damage we’ve done, you know? It’s obscene, Brian, to hear you say that we are matching the biosphere. We’re destroying the biosphere; we’re ruining the geosphere. And to a certain degree, of course, this is true, but I’m trying to say how to think about the noosphere. The noosphere is this connected-up humanity that has even changed the dynamics of biological evolution. We’ve altered things even at that level. So what I’m doing in exploring this is working with others to participate in a full emergence of the noosphere. So that that’s the promise, is that we are becoming a thinking planet, but we’re not aware of it. So we’re bringing to our activities the consciousness of just another mammalian species, you know, survive and multiply, but we haven’t yet fully grasped who we are. And I go back, and just to refer, we are the universe reflecting upon and activating itself in conscious self-awareness. The noosphere is a new understanding of why we are here, what we are about. It’s at that level. It’s one of these colossal ideas that Teilhard de Chardin arrived at in mid-20th century.

Rick Archer: Mm. I heard you say in one of your talks that humans accelerate evolution a million times faster than other animals; something you just said reminded me of that. So we’ve somehow gained the ability to, you know, go pedal to the metal. Why is that? What is it about us that enables us to do that?

Brian Thomas Swimme: What enables us to do that is the special quality that humanity has. I think it’s worthwhile for all of us, on a regular basis, to ask that question: what is it about humans that makes us special and that has led to this powerful presence? I think it’s important because it’s so essential for us to advance, and if you do it, if you reflect on it, you’ll notice that that all kinds of orientations will appear, right? Because we’ve been struggling with this question ever since human reflection began. It’s another way of asking the question, who are we? Who are we? It’s a fresh way of asking the question because now it’s within an evolutionary context. So the power that we have is symbolic consciousness, or, if you like, a symbolic language. All animal species have languages, but we’re the only species that we’ve come upon that has a symbolic language that can be expressed in forms that endure through time. So with that one move, to learn how to capture our experiences in a way that our descendants can appreciate and hold onto, with that one move, we changed ourselves from individuals into a large community. Meaning that, for instance, ask yourself where is the English language; where does it reside? Well, it’s not in the dictionaries; it’s in each of us, but it’s not contained in any one of us. The English language or human language is held by humanity, and it is this way in which we can connect with each other, and we can learn from each other. So if a deep insight occurs to a walrus one day, he can benefit from it, and he might be able to express it enough for the nearby walruses to benefit from it, but it has a tendency to die out with the death of that walrus. But our best insights carry forward. So an easy way to see what the noosphere is and to see what is special about humanity is this: we have minds that are 300,000 years in development. I mean, just think of how every time we speak or do anything, we’re drawing upon knowledge that goes back to the beginning, really, of humanity. So that’s why we are evolving a million times faster than any other species. It’s another way in which the universe has transcended itself. Biological evolution has transcended itself with cultural evolution.

Rick Archer: Do you remember that book by Isaac Asimov? It’s a short story called, “Nightfall;” remember that one?

Brian Thomas Swimme: No, tell me.

Rick Archer: It was a planet that had a bunch of suns, and it never got dark because the sun was always up, but every couple-thousand years, the suns configured themselves such that the planet went dark. And everybody freaked out and burned all the books because they had to keep the light going, you know? And so that kind of wiped out the knowledge base of that civilization, and they had to start from scratch.

Brian Thomas Swimme: (Laughter)

Rick Archer: (Laughter).

Brian Thomas Swimme: That’s a riot!

Rick Archer: Okay, so that’s very interesting. As you were speaking, I was thinking that in a way, we’ve always had a global brain or a global mind, but it’s been primitive. It’s been kind of psychotic, schizophrenic, or whatever. We’re bombing each other. We’re basically fighting against ourselves because we’re really all one family, and so there’s all this fratricide going on. And so, what we hope, I suppose, what you’re hoping is that the advancements in knowledge and technology will enable this global mind to become healthy and to stop fighting within itself. Is that a fair assessment?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Definitely, that’s what we’re working toward. Yeah, exactly. And I like — well, psychotic is a little strong, but definitely, it’s —

Rick Archer: I don’t know, there’ve been some pretty psychotic things going —

Brian Thomas Swimme: — I agree with you. I agree with you, but overall — here’s an example of what I’m trying to get across: the San Bushmen have been studied so carefully. The early Investigators discovered that, linguistically, they didn’t have a word that would be — like, when I say San Bushmen, then we’re thinking of this whole group — they didn’t have a word that pertained to all of the different groups. They didn’t have the word.

Rick Archer: Among all of their different groups, you mean?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. They would have a word for their own group, right? And there’d be a word for this other group, seen as “other,” right?

Rick Archer: But they didn’t have a word like “humanity,” like we have.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Exactly. No, exactly, you see? So that our minds haven’t yet developed even the capacity to think certain things that are required for us in order to advance. I mean, one of the ways this really came through to me was we didn’t know about the reality of extinction really until the 19th century. When philosophers would reflect on it, the idea of extinction, they would more often than not come to the conclusion it’s impossible. Now, this — I find this so stunning.

Rick Archer: The extinction of what, any species or what?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Of any species. Here’s an example of what I mean. One of the reasons Thomas Jefferson was in favor of the Louisiana Purchase is because he was hoping that we would find the dinosaurs there. Swear to God.

Rick Archer: Because he felt they couldn’t have gone extinct?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Exactly, so there was awareness of these gigantic bones, all right? And a mind as superior as Thomas Jefferson; he was one of the most intelligent people at the time. He thought the dinosaurs lived over there. You see, so the whole thing of evolutionary time had not really — here’s another one. I mean, Thomas Jefferson is one thing. Ralph Waldo Emerson, who is probably the greatest cosmologist America produced before mathematical cosmology, he was convinced that it was impossible for a species to go extinct. And then while these philosophers are convinced it’s impossible, we were already destroying species.

Rick Archer: Yes, the dodo bird went extinct around that time, I believe, and probably many others.

Brian Thomas Swimme: And then many others that we weren’t even aware of.

Rick Archer: Right.

Brian Thomas Swimme: I don’t even want to call that a psychotic mind, but it’s a mind that is so ignorant of what is taking place. And I’m talking about my mind. I mean, I think we are so profoundly ignorant of the deeper dimension of what’s taking place. In other words, we don’t have the intellectual categories to take in reality in its fullest, and maybe we won’t for a million years. In other words, this is the whole thing that I find thrilling about the way in which humanity is developing in deepening our understanding. You see my point?

Rick Archer: Yes.

Brian Thomas Swimme: I think that the atrocities that we’re carrying out are only possible because we have more development that’s needed.

Rick Archer: Yes, absolutely. I mean: “Forgive them, Father, they know not what they do.” And when you were talking earlier about the — I forget how you phrased it, but about the noosphere of being the sort of conscious unit of global mind that’s awake to itself or awake to its global nature, or something like that, the thought that popped up in my mind was okay, but there are going to have to be a lot of individuals who are awake to their true nature in order to have such a mind. Because if you have eight billion people who really don’t know themselves —

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes.

Rick Archer: — know thyself, then that’s going to reflect in the quality of the global mind, inevitably.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Absolutely. Absolutely. Yes, exactly.

Rick Archer: So that gets us down to spirituality, again, the potential it has to bring about self-realization.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. Yes. Technology is a huge part of the noosphere, but it’s not technology alone that will enable us to bring the noosphere forth in a more benevolent way. It really is spiritual development.

Rick Archer: Yes. And of course, spiritual development now is being greatly aided by technology; look at this conversation you and I are having, which we couldn’t have had even 20 years ago. And many such things, all these great wisdom teachings that, when they were originally taught, they propagated in a radius that was about as far as somebody could walk in their sandals, and over several years, and now they just flash around the world constantly.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. Yes, another indication of the emergence of the noosphere.

Rick Archer: Yes. You know, one thing I think which I’d like to hear your thoughts on is that there is some kind of spiritual awakening taking place in the world which is keeping apace more or less — maybe it’s neck and neck — but keeping apace with the exponential growth of technology. And if that were not the case, the technology alone would do us in, as it is capable of doing even now, but somehow nature — you know, there’s a beautiful thing that you talked about how the sun became 25 percent hotter over a certain period of time, and life adapted accordingly to the increased temperature of the sun. I think, correspondingly, life is adapting in the sense that a spiritual awakening is underway, which is essential to ensure that the technological explosion doesn’t destroy the planet.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, right. And I like the way you put it, that they are rising up together.

Rick Archer: Yes.

Brian Thomas Swimme: And another phrase: they’re co-evolving.

Rick Archer: Yes, and I think the technology thing has taken a step out in front of the spiritual thing, and it’s playing catch up. Because obviously, people who don’t realize this or who don’t consider the spiritual dimension, many become depressed and suicidal, or they don’t want to have children, and so on, because they say, you know, we’re screwed at the rate things are going,

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, exactly.

Rick Archer: Like that woman who sent in the question from Virginia. She was all depressed until she heard what you were saying, and then she could take action.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, let’s dwell on that a minute because that occupies a lot of us. I just think it’s important to take in, the rise in suicide and the rise in depression. I think that, going back now and to say that this relates to what I was saying before, that science can provide a pathway of wisdom, and this would be an example of it. So, how are we to feel about our present moment where, you know, thousands of species are being extinguished each year? And we’re still dragged into warfare. Now, how are we to think about that? My fundamental orientation is that we need to begin with the universe itself in our thinking. We need to establish ourselves in the universe and then do our thinking, as opposed to establishing ourselves in the economics of America or the politics of Europe or — let’s begin with something larger. Immanuel Kant was such a profound philosopher, and he made I think really a great statement. I disagree with a lot of the things he said, but in this one, he was talking about humanity needing to become new, and he said: The only way we’re going to escape the warfare and this type of existence, the only way is to develop into beings who see the whole first. I love that.

Rick Archer: That’s great.

Brian Thomas Swimme: See the whole first and then bring yourself into it. So here’s my little practice; here’s a spiritual practice for anyone who’s interested in it. So what we’ve learned, and it is really something else, we’ve learned that all of the atoms of our body were constructed by stars. Like, a carbon atom, just a single carbon atom, the only way we know we could come into existence is for a star to construct it and then explode and send it out into the galaxies. Okay, so here it is: Think of the atoms of your body, each one of them, and then recognize that each one of them comes from a star. And now go back in time before the birth of the Earth and Sun, before the birth, and imagine the cloud stretched out over thousands of light-years. And now, every atom that presently comprises who you are, presently, imagine those atoms, and imagine they have little sparkles, so you can see them; they’re stretched out over trillions upon trillions and trillions of miles. Now, suppose somehow, all of those atoms were brought together through this long, evolutionary process to become you. And the very fact that that happened is stupendous; the complexity of it blows our minds. Now just imagine if that challenge had been your challenge? What if you were responsible for getting all those atoms together? You see, at least for myself, when I dwell on just the fact of my existence and the unlikelihood of it and the complexity of it, it brings about a lightness of being it because we’re inside of forces and powers that are so far beyond us, but here we are. So that helps me; reflections like that help me escape becoming depressed by the daily news.

Rick Archer: Yes, that’s great. Organizing all the atoms that formed your body, I mean, if you were responsible for digesting your lunch, you’d be lost, or for making your heart beat over the last minute, or anything else. There are so many things that just — nature takes care of it.

Brian Thomas Swimme: And so then this would be a way, just like you say, to digest your lunch, there are patterns of that process that were actually invented three billion years ago on the Earth process. And when we can begin to, we’re going to take in that we are this construction project of the universe, you see, then, we’re learning to see the whole first. If, when we begin with the creative work that was required for us to have any relationship whatsoever, then we’re beginning with the whole, and that’s basically what I was trying to say, that science offers a new way of thinking about the whole first.

Rick Archer: Yes, that’s great. What you’ve just been saying over the last few minutes reminds me of a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, which is that: it’s established in being, perform action. That’s Chapter Two, Verse 48.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Say it again? It’s established in being?

Rick Archer: Established in being, perform action. And the implication of the verse, which the book goes on to elaborate, is that human intellect cannot possibly take into account all the ramifications of every action that we perform, all the variables and all the influences it has and everything else. But if you’re established in being, your own nature, pure consciousness — which is this, you know, I keep alluding to as the source of and foundation of the universe — then the intelligence which orchestrates the universe, which brought all these atoms together to form your body, becomes the charioteer of your life, and your life can proceed with the wisdom that you would have if you had some sort of omniscience, but you couldn’t possibly have because you’re only a human being.

Brian Thomas Swimme: I love that. Let me connect it to the noosphere. How I would see that is when the noosphere is emerging, but it is also acting. It’s acting to draw forth a behavior and forms of consciousness that will enable it to emerge further. Just to give a physical example: So hydrogen atoms, hydrogen, protons, can experience an attraction. It’s called the Strong nuclear interaction. So this attraction, what scientists have learned is that if this attraction is altered, even as much as two percent, then long, burning stars become an impossibility, just so that even in a subtle way, at the level of protons — again, this would be in the thinking of Teilhard de Chardin — that the attraction we feel is the future working to bring itself forward. So like you said, and again, I can’t quote your words exactly, but “Established in being, perform action.” So that if, if one is established in being, well, then this would be from the point of view of the noosphere, that where we are today, in this moment, is being in part orchestrated by our own deepest fascinations. So what we find ourselves fascinated by is the noosphere drawing us into activity that will make its embodiments clearer.

Rick Archer: That’s great.

Brian Thomas Swimme: You know, the spiritual development is expressed differently with the noosphere, but it is profoundly similar to what you were saying about the Bhagavad Gita.

Rick Archer: Yes. The reason that verse came up was that Arjuna couldn’t figure out what to do. He was in this quandary where his heart and his mind were in conflict, and he just didn’t see a path of action that he could take. And Krishna, who was advising him, said, well, you’re right, and you can’t figure it out from a superficial level, the level of human intellect alone; you have to take recourse to a much vaster intelligence which resides deep within you. Get established in that, and your action will spontaneously do the right thing, even if you wouldn’t have been able to work it out otherwise. And what you’re saying about the noosphere, I gathered that there is a collective intelligence which is more than the sum of its parts, just as our body is more than the sum of its cells, and that it has an intelligence of its own, just as our body has an intelligence of its own. And, you know, we as an individual don’t totally grok that intelligence, just as an individual cell in our body doesn’t realize what the whole collection of cells is doing, or an ant in an ant colony or a bee in a beehive. But the collective intelligence governing the earth or in our body, in the case of that analogy, has the wisdom to work it out. And I suppose maybe you would say that what we have to do in order for the noosphere to really wake up is attune to it as best we can, so that we align with its intention. In fact, there was some quote I pulled about aligning here. Where is it? Ah, “Humanity acting as a whole might act in ways that are harmonious with life.” There was something else that you said was beautiful about aligning one’s individual intentions with the global intention of the noosphere in order to enable it to realize its full potential.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, let me —

Rick Archer: Oh, here it is. I found it. “Are we aligned with Earth’s primary aim, which is to construct a planetary mind? That’s the question that we should ask ourselves.” There you go.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Okay. Yes, I let me dwell on that because I — do I use the phrase Earth’s primary aim?

Rick Archer: That’s it. You did, yes, I pulled that from one of your videos, I think.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Okay. Yes, I believe I said it, but I want to approach it from a slightly different angle and say the same thing, but I’ll tell you right away with the angle is. I think we have a dual aspect to our nature, in that each of us is just this person who lives in a certain place and has relationships, and so forth and we are the manifestation of something vast. And that language here would be different, but I’ve already said it a number of times. So we’re individual people going about our day, and we are a cosmological construction that required 14 billion years, simultaneously, at the same time. So that it’s a question of what is the primary aim of Earth, and how does that relate to our daily lives? So here’s, I think, so far, this is this is the best example I have of conveying what the noosphere is, the best example I have, and that is the James Webb Space Telescope.

Rick Archer: Yes, I quoted that. You said, “The noosphere built the James Webb Telescope.” I pulled that out of that.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. And even though the noosphere is a complex idea, it’s also a simple idea. And what I like about it, it makes it really, really clear. I started off saying, imagine ourselves back 300,000 years. So just imagine ourselves back then. And I’ll bet you anything, people were looking at the stars and going, what’s going on? And they would think about it, because they’re so compelling for humans, and that interest in the stars continues for all 300,000 years. So, already, my first point I want to make is this: that’d be an example of a primary human urge. The primary human urge is to understand what’s the nature of where we are? But a couple of interesting facts about the James Webb Space Telescope. It was constructed by engineers in 14 different countries, and they put together all their skill and knowledge and built the James Webb telescope. So each of them is essential, but not one of them alone can do it. But think of this; hold it. Each of those engineers had to learn from their teachers — grade school, high school, college — and those teachers were passing on knowledge that had been formulated millennia in the past. So they’re essential for the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. So were the farmers to feed them; so are the political figures that kept society ordered enough so that this human development could take place. And so if you, just in the most obvious way, a billion humans — you’re going back through time and the present today, could look at the James Webb Space Telescope and say, we built it. It was all of us, with each one being essential. So that’s an example of the of the noosphere in action. It is accomplished. The James Webb Space Telescope is a hundred times more sensitive than the Hubble. I mean, there’s no question but we will learn things about the birth of the universe never learned before our time. A lot of scientists are very confident that we will be the generation that identifies living planets. There’s something like 50 billion planets in the Milky Way Galaxy; around 300 million of them are Earth-like. So those are going to be examined carefully, and we will be able to establish if they’re living or not. In other words, my point is, just think of this knowledge; think of what we’ve learned compared to what we knew 300,000 years ago, when we were just kind of, like, amazed by the stars. So this is the noosphere in action, and it was satisfying a deep urge in humanity, the urge to know the nature of the universe, the nature of where we are. But here’s my last point. There are other primordial urges; I don’t know how exactly to name them, but there’s the urge to educate; there’s the urge to heal. There’s the urge to build structures that protect us. And there’s the urge to forgive. We have a deep desire to forgive and make amends. So if we think of these primordial human desires, and they are being fulfilled by the noosphere, by the human collective, we get a sense of what it means to be human; we get a new sense of what it means to be human. That would be the simplest way I know to give an explanation of the noosphere as a collective.

Rick Archer: Yes. You actually just gave me a much deeper appreciation of it than I’ve had so far. And I watched all the videos on your Human Energy Project site, and I’ve been thinking about the noosphere all week. But what you just said, actually, you know, it really hit home.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Can you say what was new? I’m curious as to —

Rick Archer: Well, as you were saying, it, I got a more visceral feeling of the noosphere as a single entity, of collective consciousness as a single entity. And I thought of the great James Webb telescope as a, like we’ve grown a new eye, you know —

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, yes.

Rick Archer: — which is so much more sophisticated than the eye we had or the eyes we had. And then you mentioned other things like healing and various other things. And so, these are all potentialities which we, as a global being, need to grow or need to evolve beyond where they are now, and we can only do it together. You know, what you just said about the Webb I remember was also said about the moon landing. Someone said, well, nobody knows exactly how we did it because it had to be so compartmentalized because there was so much involved, no one person could have contained all that knowledge. So there are certain things that just have to be collaborative efforts or endeavors. And it’s just exciting to think of how, if we could just get our act together and be more harmonious as a species, oh, how much profoundly more we could accomplish. Because as it is now, we just waste so much time and energy and resources fighting each other and ripping each other off in various ways, and you know, wealth inequities, and all these other things. I mean, if we could really become harmonious, we could just really literally reach for the stars.

Brian Thomas Swimme: And what’s so great is to reflect on the fact that what we will bring forth even goes beyond our ability to understand now. It’s “un-pre-thinkable,” in Schelling’s terms, and it gives a thrill for being alive. That’s why I so want to get to the people who are depressed by our situation that great things are happening.

Rick Archer: They really are. And again, if we think of the noosphere or our collective consciousness of humanity as a single entity, then, you know, there are cancers within that entity which are gobbling up more than their share and usurping the territories of other organs in the entity where they don’t belong, and things like that. So anyway, we can play with the metaphor, but you can imagine a really harmonious collective consciousness and how there would be this feedback loop between the whole and the individual and the whole and the individual, kind of enriching each other beyond what we can imagine, perhaps.

Brian Thomas Swimme: It’s so important, what you’re saying, the feedback.

Rick Archer: Yes.

Brian Thomas Swimme: It’s not some amorphous thing out there. It’s a deepening collective intelligence which activates an individualistic intelligence; both happen simultaneously.

Rick Archer: And the individual intelligence enriches or enlivens the collective intelligence. So it’s the —

Brian Thomas Swimme: The back and forth, exactly. Yes.

Rick Archer: — this loop. Yes. And it works both ways. You know, if we keep spewing out negativity and incoherence, then that comes back to us.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, exactly.

Rick Archer: But you know, this thing you said about not being depressed and suicidal and all that and not giving up hope, I don’t think anybody has to wait for all of humanity to get their act together in order for them to get their act together. So you know, no matter — and of course, a lot of people have it tough. I mean, you’re born in harsh circumstances or something, and you don’t have the educational opportunities, and so on. But within the context of wherever we find ourselves, I think there’s always room for exercising one’s intention, one’s free will, and progressing to a great extent.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Completely. That brings to mind that statement: If you ever think that one small individual — no, go, go ahead.

Rick Archer: No, what’s her name? You go ahead.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Okay. If you ever think one small individual can’t make a difference, try to sleep with a mosquito in the room.

Rick Archer: Oh, that one, okay, right. I was thinking about —

Brian Thomas Swimme: It’ll come back.

Rick Archer: — yes. Yes, that’s a good one. I was thinking of some Margaret Mead quote where she was talking about —

Brian Thomas Swimme: Oh, yes. If you think a small group can’t — and, yeah.

Rick Archer: Yes, can’t make a big change, that’s the only thing that ever has, or something like that.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, yes.

Rick Archer: Good. Okay. All right. We got our quotes out. A question came in. Let me just ask this question to you. It’s back to Thomas Berry. Someone named Thomas Sullivan in New Hampshire wants to know what your opinion is of Thomas Berry’s book The Dream of the Earth.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Oh, this is Thomas Sullivan?

Rick Archer: A Thomas Sullivan in New Hampshire wants to know what your opinion is of that book.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. I think it’s one of the greatest books that I’ve ever read. I just love it. And it may be that because I was raised in a Christian family, a Catholic family, it had special significance for me, so I can’t speak for others. But he just, he saw through so many of the superficial temptations that we’re prey to, and he gave an interpretation of history that is remarkable. So I highly recommend The Dream of the Earth to anyone who has a sense of our moment being a pivotal moment of moving into another era of humanity with a new sense of the sacred and is profoundly ecological. He was one of the first people to use the phrase, “integral ecology.” He saw ecology as an entire interpretation of the universe.

Rick Archer: The other thing I wanted to ask you about is — here are a couple of quotes that I lifted from your videos: “Polarization is a symptom of our having entered a phase transition.” And here’s another one: “A good deal of chaos will accompany the transformation.” So there’s a lot of polarization taking place these days, particularly in American politics, but I imagine in other realms, and there’s a good deal of chaos, and there could be a good deal more. I was just reading the other day about some giant glacier in Antarctica which is in danger of breaking loose and raising sea levels a couple of feet. That will be huge if that were to happen. And so as you watch current events and read about things like glaciers in Antarctica, and so on, are you able to put a positive spin on it in the sense that you see these things as symptomatic of a phase transition taking place, and that better times are a comin’ or what?

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. Well, the challenge is not to sink into despair when we really take in what’s happening today. Going back to Thomas Berry, he said — because we would talk about the despair — and his phrase was, “Despair is a luxury we can’t afford.” But nevertheless — and we’re talking about spiritual development — again quoting Thomas Berry, he said that “the first benefit of spiritual development is the strength to endure the chaos of our time.” That’s always meant a lot to me. One more quote, and this is one of my all-time favorites, and it relates exactly to your question. It’s actually from Alfred Kroeber, an anthropologist at UC Berkeley. He’s the one who found and worked with Ishi, the last — the wild Indian. Anyway, what he said was: “The ideal state for the human is not exactly bovine placidity. It is rather the highest degree of tension that can be creatively borne.” And that’s always meant so much to me, because we do have, in America at least, there’s a strain of wanting bovine placidity. It has to do with the drive for material wealth, money, as a way of being done with all of that tension and hardship of life and then just securing yourself inside of a palace and then watching media, and, you know, it’s a kind of bovine placidity. But what we need is creative leadership in the midst of this, and just to be able to — this is the noosphere in action. It’s delivering to us the extreme states of suffering all around the planet. And in no way will I say that these are somehow a good thing. I want that understood very clearly, that it’s absolutely horrific. However, because it is taking place, it can serve you. And now, just speaking to anyone who’s disturbed, because the transformation that Rick and I have been talking about throughout our conversation is a deep change, a deep change of heart, a deep change of mind. It’s coming to a fundamentally new insight into what it means to be human. And it’s hard to change one’s fundamental orientation in the universe. It’s extremely difficult, but the suffering that’s taking place on the planet can be beneficial if you allow it to break down those structures of your existence that are actually participating in the violence. It does have that power, when you suddenly realize you can see through all the false allurements of contemporary society and see into what is essential. You can awaken to the whole and what your role might be in the midst of it. So that’s basically how I respond to the difficulty. I try to hold it in my heart and wonder in what way can I be part of the solution?

Rick Archer: In the Hindu mythology, Shiva, the Destroyer was regarded with as much reverence, if not more, than Brahma, the Creator. It was understood that destruction is part of creation, and sometimes things have to crumble in order for something better to come along. I mean, exploding stars is a good example.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes, yes.

Rick Archer: Anyway, when stars explode, there might be populated planets around them. And eventually our star will grow to engulf the Earth, and it won’t be pretty if you happen to be around when that begins to happen. But in the big picture, there’s evolution taking place.

Brian Thomas Swimme: That’s right.

Rick Archer: Yes, the first time I ever met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, it was at a course in 1970, and he was talking about the pace of change and the pace of society and how it’s getting more and more intense. And he said, if a donkey is required to carry a heavy load, and the load gets to be too much, there are two things you can do: lighten the load or strengthen the donkey. And he said, unfortunately, we can’t lighten the load in terms of what the world is undergoing. It’s just going to get more fast- paced. But he said, we have to become stronger from within. And then —

Brian Thomas Swimme: Nice.

Rick Archer: — yes.

Brian Thomas Swimme: That’s nice — strong enough to face it.

Rick Archer: Yes, strong enough to be able to actually benefit from it, as that quote you just said. It reminded me of Nietzsche saying that whatever doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes.

Rick Archer: When you think about it — what do you think about this? There are so many things that exist in today’s world that really couldn’t or shouldn’t exist in a more ideal world, and some of these things are major pillars of our economy, and so on. So somehow or other, if we’re actually going to shift to a more enlightened world, those things are going to have to transition in some way, and it may be rather disruptive.

Brian Thomas Swimme: Yes. Just to comment on that point, I remember when I learned there’s a breaking of symmetry in the early universe — it’s kind of quick; I can do it quickly — that our thinking about the early universe was that matter comes out of the quantum vacuum; I mean, there’s no doubt about that. But the strange thing is that in the early universe, there was an asymmetry to the emergence of these elementary particles. Protons emerged; antiprotons emerged. And when a proton and an antiproton come together, they disappear into light. But the bizarre thing is that in the early moments of the universe, with all these particles bubbling out of the vacuum, there was an asymmetry, in that for every billion antiprotons, there were a billion-plus-one protons. So that, the idea is that the universe had a billion times more matter at the beginning than it did a little later. I remember learning this and thinking, that is so bizarre and strange. But then a similar thing, and this is the last one I’ll mention about this, is that the number of species alive today is only one percent of the number of species that have come forth. And as a young person, I thought, that’s just so bizarre, that you’d extinguish 99 percent of life in order to get to the human; that’s how I was thinking. But nevertheless, the fundamental error I was making was that I thought I could do things better. I thought, if I were in charge, I would just have, for instance, I wouldn’t have all the protons and antiprotons annihilating each other; I would just start out with the protons I need, right? And then when we get to Earth, I wouldn’t have all these species fluttering in and out and going extinct. I would just get some dirt, bring it together and make humans, you know, the simplistic way of interpreting the Bible. So this goes back to the very early part of our conversation. We get these intuitions that we live inside a field of intelligence, but it’s an intelligence we don’t understand, because it’s different from human intelligence. And so, I am not saying that the disasters are a good thing, but they are part of what’s taking place. I love that with the honoring of destruction in Hinduism, as you just said.

Rick Archer: Yes.